The Semmelweiss Reflex – Rejecting New Evidence Opposing Established Norms

The new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.

Max Planck

Kurt Vonnegut called him “my hero.” His birth house is now a museum named for him. Many wrote about him, and last year, over 150 years after he died, there was a play about him in London. But Dr. Ignaz Semmelweiss did not enjoy this popularity when alive.

After earning his medical degree, Vienna General Hospital appointed him to their First Obstetrical Clinic in 1846. Made of 2 units, the 1st clinic, run by midwives, had a much lower mortality rate than the 2nd, operated by doctors. After much research, he suspected that doctors going from their cadaver lab directly to the maternity ward might have led to the transfer of “cadaverous particles” to maternity ward patients, as midwives in the 2nd clinic had no such contact with corpses. He suggested that doctors wash their hands. When they initiated that procedure in the first clinic, its mortality rates plummeted.

However, colleagues broadly mocked his hypothesis that only hygiene mattered. At the time, his theories lacked scientific explanation. That became possible after his death when Louis Pasteur and others developed the germ theory of disease.

Outraged by the apathy of his colleagues, he became dejected and drank heavily. He was committed to an insane asylum where guards beat him until his hand got gangrene, which quickly killed him.

The rejection of his observations was so severe that it came to be named the Semmelweiss Reflex, the affinity of people to cling to discredited beliefs.

I know something about that. I’ve taken my book to some big-name graduate schools. They won’t say it’s wrong. They just won’t read it. Thus, I’ve seen my paradigm-shifting observations undisputed but largely ignored. That reaction persists despite my undeniable mathematical evidence proving those previously held theorems false and incomplete.

At the lower left below, here’s an example homework problem for a current economics class that wants students to explain a “change in market equilibrium.”

Note the complete lack of data. Everything in the diagram is imaginary. Where is the information about the cars? Nonexistent. Oops.

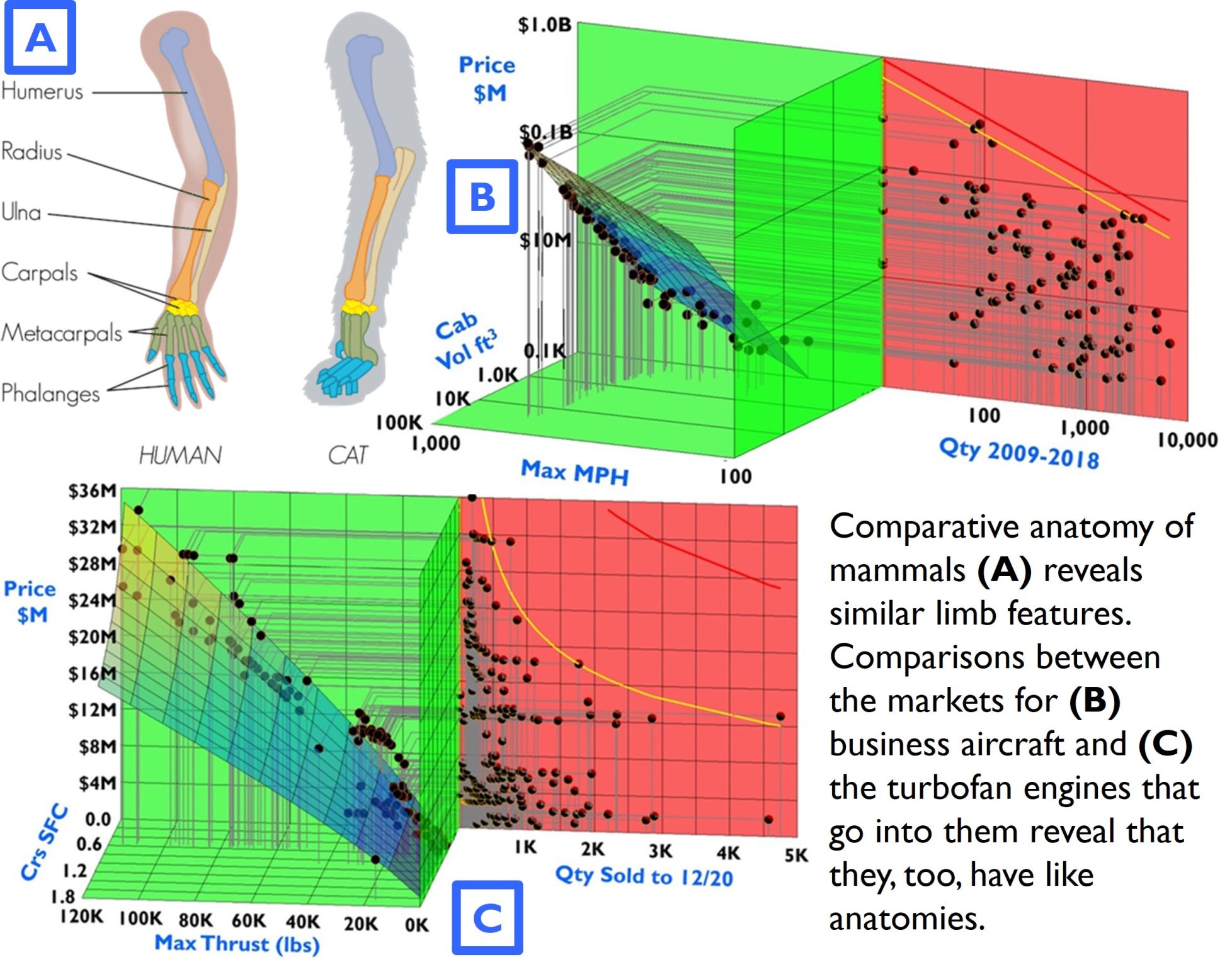

Markets form with actual data, as shown in the lower right diagram. There, 18 electric car models for sale had points in Value Space (green spheres) describing their 1) Range, 2) Horsepower, and 3) Price, with matching points (red spheres) on the Demand Plane depicting their 3) Prices and 4) Quantities sold. There is no “equilibrium point,” as models enjoy “sustainable disequilibria” when prices exceed costs.

Unlike Dr. S, the rejection won’t drive me mad. But I am curious about the apathy.

And I wonder, as Semmelweiss did, who will wash their hands first?

#semmelweiss #hypernomics